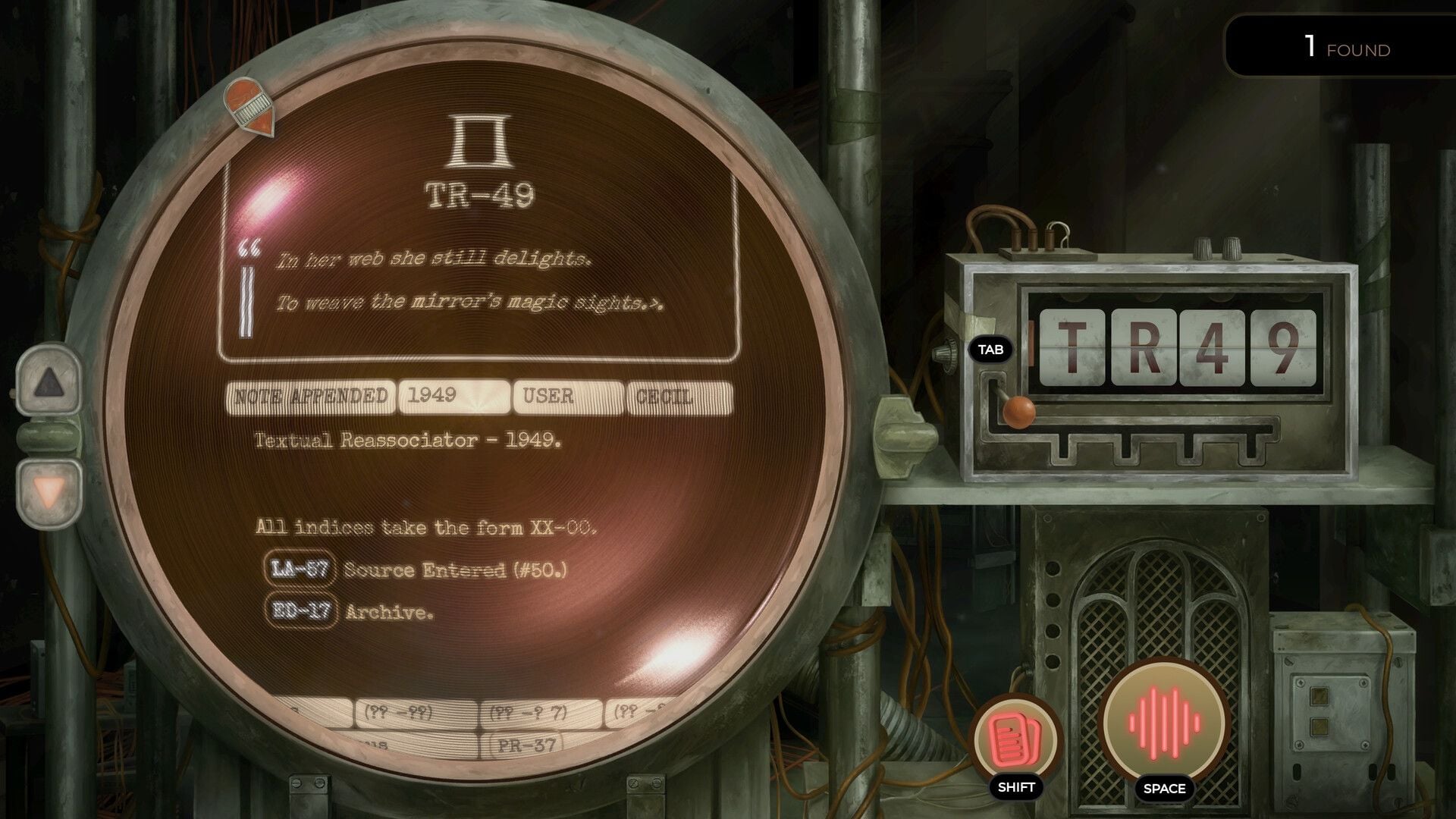

TR-49 is analogy rendered in four dimensions. On a surface level, it’s a game about sorting through an archive of written works and commentary that has you identifying dozens of excerpts and documents, all with the aim of destroying a particular work. Beneath the surface, however, this is a piece of art that speaks viciously and satirically to so much of our reality.

TR-49 casts you as Abbi, a woman who must come to grips with a peculiar computer seemingly built from salvage, in order to identify and eliminate a specific piece of writing. Something is very wrong in this alternative version of the UK, however; war is raging outside, and for some reason finding a specific digitized version of a book is going to make a difference. At the beginning of the game you will have about as much understanding of how to go about locating the essential text as you might how to fly a plane. If you’ve played Type Help or perhaps Her Story you’ll have some instincts in place, knowing to just search the database for what you can see and keep going until its disparate aspects begin to come together. You may also find yourself troubled by a strong sense that you must have missed something. You haven’t. Keep going.

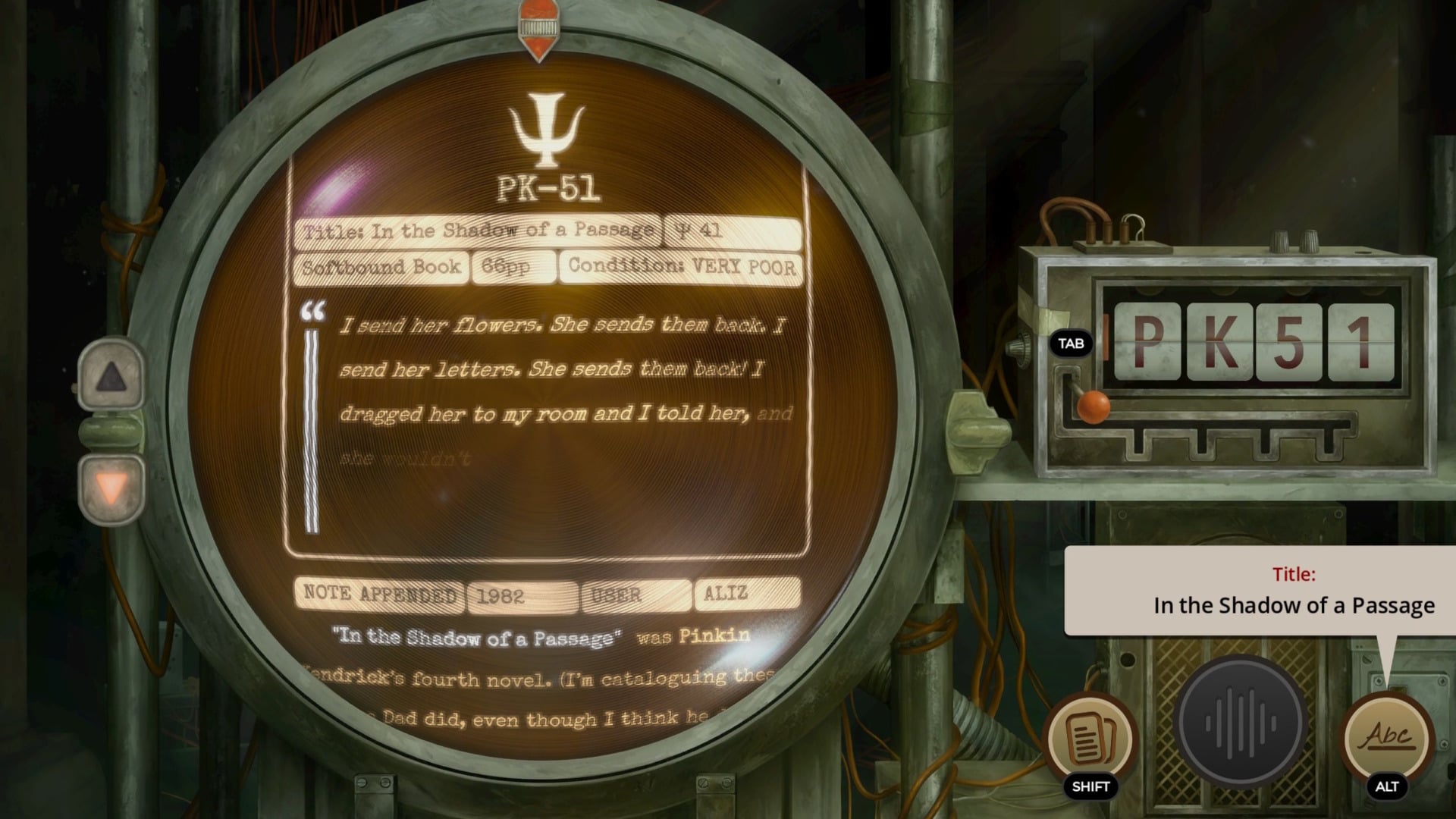

I’m reluctant to talk any more about what you do in this remarkable game, because all that can do is rob you of the same sense of a slowly redeemed helplessness that I was able to experience. And not just for the sake of gaming puritanism, but because that experience is so integral to so much of what the game is about. It’s safe to say that you have a visual archive of many dozens of texts (and accompanying commentary notes) to explore, and that as you go you begin matching titles to documents as well as amassing an automatically filled in collection of sublime notes that mean you can get from start to finish without ever needing to grab a pen.

It is far more interesting to discuss what exists beneath TR-49‘s mechanics, the wealth of meaning to find if you pierce the veneer. Despite its alt-history setting, depicted in an ancient, grimy stone basement, and documents primarily from the early-to-mid 20th century, this game feels incredibly, painfully relevant in 2026. This is no simple, reductive allegory, but rather an extraordinary tangle of interwoven analogy. It’s as much a piece about the existential threat posed by the mercenary consumption of human-created works being done by gen-AI as it is the immediate danger of a government that refuses to adhere to reality, although you could equally read the work as being about the complexities of constructivism, epistemology, and linguistic relativity. Heck, it’s a giant machine that eats books. Or you could just enjoy it as big, difficult puzzle.

As you explore the archives you’ll learn not only about the progression of writings by a range of fictional academics and authors, but also the family and relationships of the people who built the machine you’re using and the effects the archived texts have had upon them. The game walks an incredibly fine tightrope with enormous finesse, delicately entwining magical realism into an all-too recognizable dystopian present.. It forces you to think. Not think about how to solve the puzzles, although of course it does, but to explore ideas you might not have considered before.

I’m not going to pretend to have read about, or even have heard of, linguistic relativity and the so-called Whorf-Sapir hypothesis before playing TR-49. But as a result of playing it, and needing to discover a vocabulary to describe ideas it provoked, it’s where I’ve ended up. That hypothesis is the argument, if I can oversimplify it to the point where I understand it, that it is our language that determines our cognition, rather than the other way around. Is that true? Does it get dangerously close to some sort of linguistic eugenics? A magically realized view of the concept is described in the texts of the articles and publications you uncover, and weaves a whole new fiction, a sort of linguo-punk 20th century, one that critiques and speaks to the apocalyptic reality of the game’s present. And please understand it does this with no self-importance, no ostentation, instead delivering it like the hum of a machine you only realize you were hearing once it switches off.

There is an irony in the fact that TR-49‘s greatest weakness manifests when it attempts to impose its narrative upon you far more forcefully. Alongside reading through the texts and deciphering the codes needed to unearth more, you also have the vocal company of a man called Liam, somewhat instructing the bemused Abbi as to what she needs to do (albeit mostly by telling her that her confusion (and yours) is part of the process). After Liam speaks, a button resembling a speaker glows pink, encouraging you to click it and thus have Abbi respond. Quite why you have to constantly prompt the responses is unclear, and it quickly becomes surprisingly irritating while you’re attempting to fathom connections between texts and infer information from wonderfully subtle clues. On far too many occasions I yelled at Liam to “just shut up!” while I was trying to play, feeling obliged to deliver Abbi’s responses, having to endlessly click on the button instead of the document I’m scrolling through, all for a conversation that doesn’t really add very much.

-

BACK OF THE BOX QUOTE

“Linguo-punk mastery”

-

TYPE OF GAME

Alt-history dystopian document discovery

-

LIKED

Extraordinary world-building (and dissembling), eventual sense of feeling awfully clever, stunning music

-

DISLIKED

Liam talking when I’m trying to think

This is no criticism of the writing and especially not of the excellent voice acting—it’s just that it’s so often so incongruous to what I’m trying to do. Liam just pipes up while I’m mid-thought, throwing me off my flow, and I began to resent him for it. There’s a moment very early on when Liam has to step away from his microphone, and Abbi panics without him but I was enjoying the peace and quiet. (It’s even more annoying that Liam’s interjections speak over the rest of the splendid voice acting of identified texts being read aloud.) It is a shame to find myself so irritated by the main characters with whom I’m supposed to relate.

However, as I hope is obvious, this splendid game remains well worth your time. And for those who, like me, find themselves utterly overwhelmed by the likes of The Case of the Golden Idol and Obra Dinn, where the volume of information you’re asked to juggle becomes white noise to my ADHD-addled brain, I encountered none of this with TR-49. I credit this to the (I already called them “sublime” but there’s no better word) sublime automatically updated notes. They give nothing away, but they allow hundreds of disparate pieces of information to be calmly ordered.

It is perhaps about time we stopped being surprised by just how brilliant each new game from Inkle is capable of being, but I’m still delighted by how different TR-49 feels from, say, Sorcery!, Heaven’s Vault, and Overboard! Each game is an extraordinary demonstration of a mastery of language, and TR-49 is no different. Except it’s very different, not least in its paranoia over the power of language, its potential dangers, and indeed the explicit dangers of its exploitation and censorship. 2026 is a chillingly perfect time to release a game about a machine that learns the atomistic contents of books, destroying them in the process.